James Dixon

1887–1970, Irish

Tags: Painting

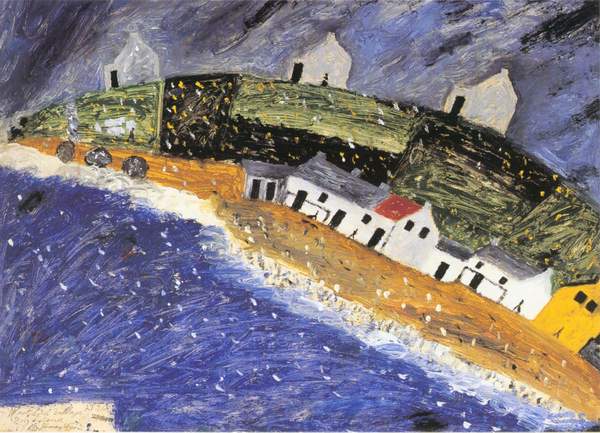

A small outpost of civilization in the Northern Atlantic, Tory Island was described by Richard Ingleby as “an isolated finger of land nine miles off the coast.”(1) The rocky cliffs and rugged terrain of this Irish island were where James Dixon spent his entire life, first as a sailor and fisherman, and later as an admired painter.

Dixon was born on Tory Island on June 2, 1887. His mother was a native islander and his father came from County Donegal on the Irish mainland. There were six children in the family, one of whom eventually left the island to live in the United States. Or, as Dixon said, to live in the next parish, meaning Connecticut.

Portfolio of Work

Click Arrows to View More Artwork

The population of the island is quite small, under one hundred fifty permanent residents, although outsiders would sometimes spend summers there. One of these regular visitors was the renowned English painter, Derek Hill. Summarizing the isolation of the land, Hill writes in an essay: “John Berber, the critic referred to Tory Island as being like a boat adrift with wreck survivors, but with no hope of ever reaching the mainland.”(2)

The meeting of James Dixon and Derek Hill is an oft-repeated story, evolving into something of a legend. One Sunday, Hill was painting outdoors as a crowd gathered to watch him work after church services. Dixon was in the crowd watching, and said, “I can do that.” So, Hill gave him some paints and also some brushes which Dixon refused, as he preferred brushes made from hair of his donkey’s tail. When presented with the results, Hill was quite impressed and a lasting friendship was formed. Commenting on Dixon’s choice of brush, Hill says, “This last factor seems important for his work as it helps, I think, to give the painterly quality one finds. They are all painter’s pictures and not merely picture making…”

It was assumed that this meeting between Dixon and Hill in 1956 or 1958 was Dixon’s first foray into painting. However, there are Dixon paintings that were received by Wallace Clark, an Irish yachtsman, historian, and visitor to the island prior to this date. Thus, the early history of Dixon’s art is reconsidered. Sara Glennie and Michael Tooby write:

“It can be read that Dixon’s comment on meeting Derek Hill, “I could do that”, was the catalyst for his painting, but he was in fact painting before this meeting between 1956 and 1958, giving paintings to Wallace Clark, a regular visitor to Tory Island, during the 1950s. This knowledge turns his claim into a confident challenge rather than a flippant remark on stumbling across a painter. Also, his decision to use donkey-hair brushes can be seen to derive from experience, not eccentricity.”(3)

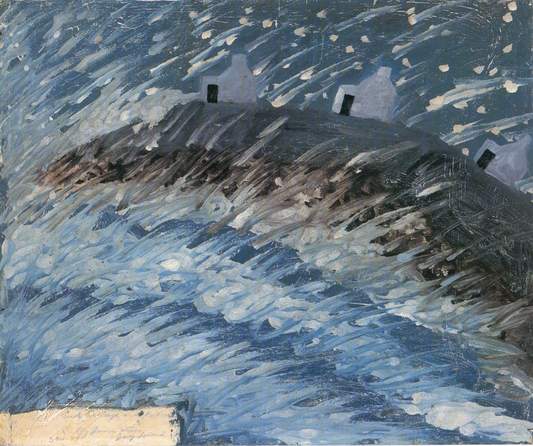

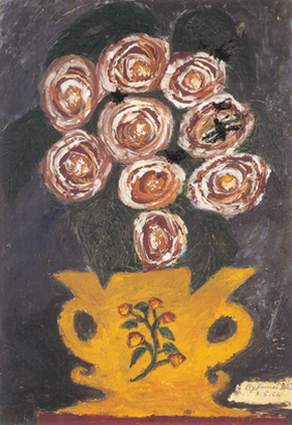

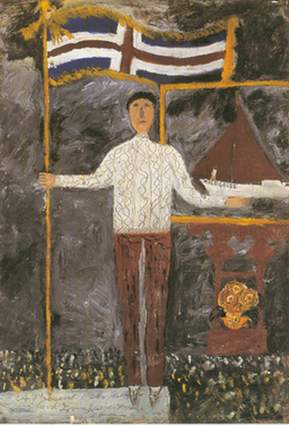

The painting that Hill was working on at the time of their meeting was West End Village. Dixon composed a piece with a similar title in response to Hill’s gift of supplies, though the paint Dixon usually used was leftover boat paint applied to paper or board. The subjects of James Dixon’s paintings are reflective of his life on Tory Island, both in the daily activities of an islander and the objects of everyday life, rendered with meaning through his painterly vision. Raging seascapes, portraits, religious imagery, and even still-life are all types of compositions seen in his work.

Often, a note of narrative humor or candor can be seen in his work. In the painting Arlin Point, an inky, abstract figure stands at the top of the peak. In pen, a little more green than the swirling sky, is an arrow and a notation, “Mr. Hill”. Dixon included Derek Hill standing outside his painting cottage in this picture, a counterpoint to the foreground action where an overwhelming fish pulls a helpless boat of sailors. The paint is built up in a shallow impasto in some areas, and even incised to describe the net around the great fish. A geometric man and his donkey are also etched in the thick paint as they follow a large black van up the path. Small puffy sheep dot the hill in a design and decoration of shape, becoming as much a part of the landscape as any tree or rock would.

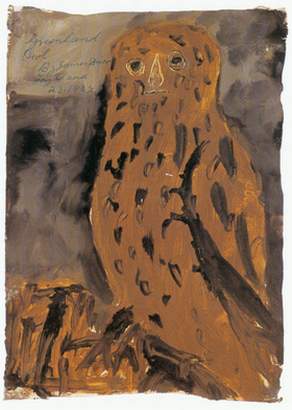

Many of James Dixon’s works have dates and descriptive titles that provide clues to his personal account of the subject matter. The strong brushwork and bold shapes that make up his compositions can be seen as an expressive extension of the powerful forces that shaped the island he called home for his entire life. The character of Dixon’s paintings stems from the energetic handling of the paint, but there are small, hidden details, overwhelmed at first glance by the dominance of larger forms and shapes. Even Dixon’s still-lifes have a massive quality, such as Loving Cup. Yet this picture, for all its assertiveness, still retains a poised beauty and awareness of nature, seen in the hidden insects flitting about the flowers in the bouquet.

Dixon’s long-time friend, Jill Livsey, provides insight into his character and other creative talents. For the book, Self-Taught and Outsider Art: The Anthony Petullo Collection, she wrote this essay:

A man of versatility, Jimmy was also a reader, rifle-shooter, and taxidermist. He harvested crops with a sickle and made model boats, a jeweled walking stick, and jewelry. Often, when a fierce gale would rage for days on end, he would go to his workshop and produce dramatic pictures. Above all, Jimmy had a deep Christian faith. His kindly philosophy still encourages me today. As well as being a true artist, he was resilient, perceptive, and a kind-hearted man.(4)

Through the admiration of Derek Hill, Dixon’s work became known to a larger art community in mainland Ireland and England. Dixon often sent paintings to Hill which arrived, still wet, and had to be peeled apart from each other. He has been shown in numerous exhibitions, the first solo exhibition was at the The New Gallery in Belfast in 1966, followed by a November exhibition that year at Portal Gallery in London. Recent major shows include Two Artists: James Dixon and Alfred Wallis which was seen in Dublin at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and at the Tate Gallery St. Ives in 1999 and 2000.

James Dixon died on Tory Island in 1970 and was buried in the cemetery along with his other siblings and family members who had spent their lives on the island.

Dixon’s work was exhibited in Belfast, London, Dublin, and Vienna during the three last years of his life. A seminal exhibition in 1999–2000 at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and Tate Gallery St. Ives paired his work with that of Alfred Wallis, a self-taught artist who also portrayed seafaring life and the terrain of a coastal region of the British Isles.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Two Painters (London: Merrell Holberton Publishers Limited, 1999)

Clark, Wallace. Sailing Round Ireland (London: B.T. Batsford LTD, 1976)

Hill, Derek. James Dixon: Paintings of Tory Island (Cambridge: Benet Gallery, 1967)

Petullo, Anthony. Self-Taught and Outsider Art: The Anthony Petullo Collection(University of Illinois Press, 2001)